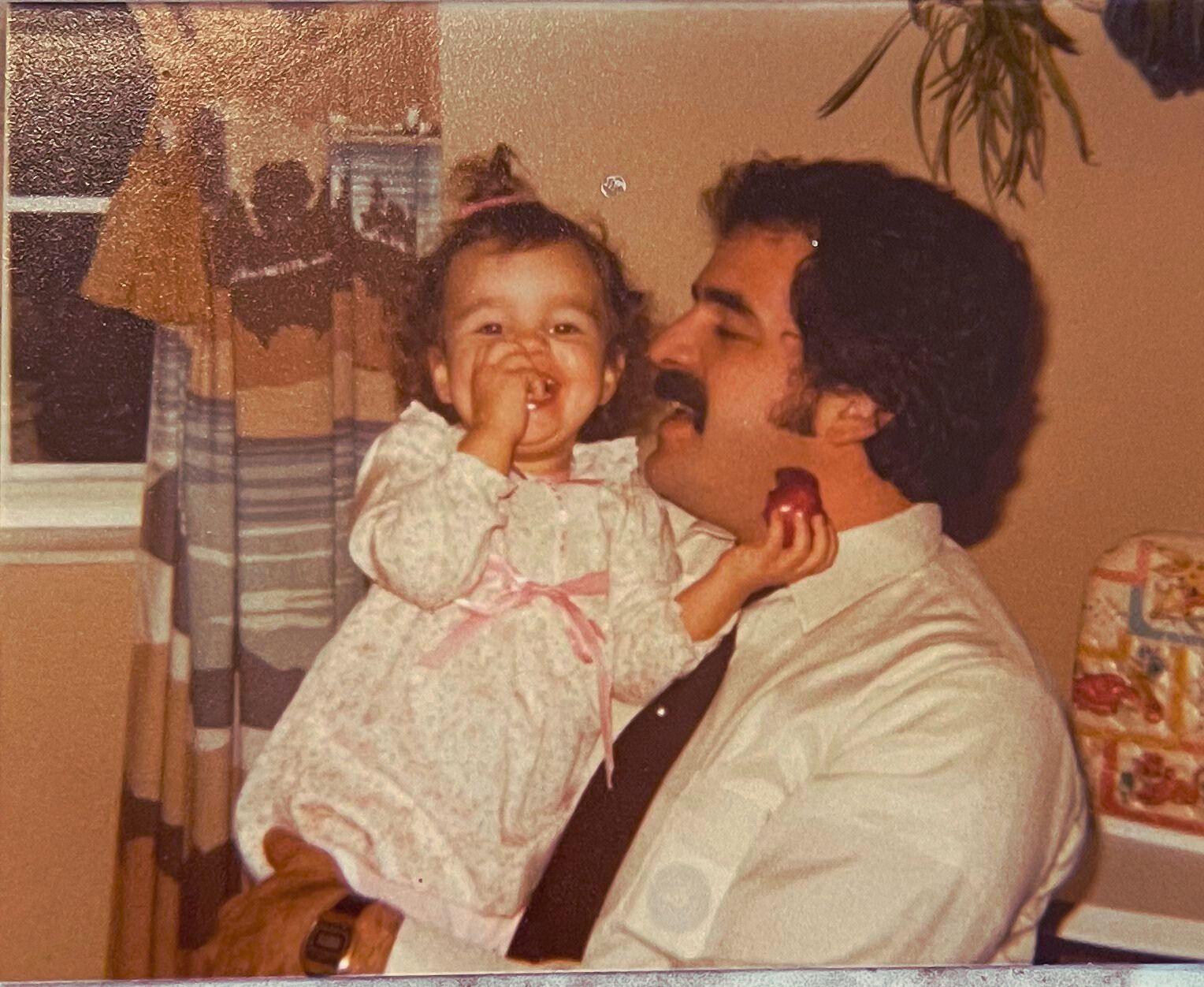

Let me introduce myself (and I guess I’ll start with my nicknames too, since my sister already did). I’m my dad’s curly-haired baby girl. His youngest and most sensitive. His adventurer and his spiritual seeker. The one he named Tracy because it sounded a little like the name “Benny” he’d picked out, hoping that his second child would be a boy. I was not the boy he hoped for—my big sister got that job—but the name Tracy soon became Baby-T, Teeter-Teeter, TT, or simply T, later Evie-T, then, in 2006, I was gifted the name Isha by my teachers in Colorado. My dad rolled with Isha-T. But mostly, he always called me his curly-haired little girl.

My sister has continued this nicknaming legacy, transforming TT into Tater-tot, Potato, Patti, Patti-Cakes, Patti La-té, Chef La-lé, and for Megan, Nick, and Nate, I’m Aunt Weve. To everyone else, I’m Isha.

My dad had many sides. We all do. There’s a spectrum of qualities in our personalities from which we express ourselves daily. But it seems my dad could play a fuller range of expression than most. Like notes on a trumpet, he played big, loud, and off the scales. He didn’t practice. He’d be the first to tell you he was already the greatest trumpet player who-ever-played-of-all-time as he was the greatest at everything he ever attempted. This included his inventions.

“Check this out,” he’d say. Then proudly display his latest and greatest invention, which could range from elf shoes, incense burners, wooden bowls, his Emley Bar (ask a firefighter in the room), to his lawnmower-powered blender for margaritas, to the parade float he helped build of a giant Cobra snake dribbling a soccer ball for my team—which he did while wearing, of course, his elf shoes. Speaking of parades, let’s not forget the shortest parade of all time, which he hosted on his own street with an old toilet he mounted as a throne, which he, of course, sat upon with great pride, as he rolled briefly down to celebrate himself as the newly self-elected Mayor. Don’t forget his wild boar hat, or the homemade Viking hat filled with maggots, because he neglected to dry out the bull horns. You could sit up all night telling his stories and barely make a dent in his catalogue of life, and he hopes you do.

In my 46 years of knowing him, I witnessed a few of his other sides. He was, first and foremost a Lieutenant Firefighter from the 52s, the heavy rescue squad, with all the wild courage and camaraderie that accompany that identity.

My dad could be outrageous and quick to best anyone who dared challenge him. He could be alternately absent or angry, out with his “boys” or home with a temper that could transform plates into flying saucers (I have firsthand experience with this).

In his absence, the 24-hour shifts “on” at the firehouse, nights out with his “boys” or on his motorcycle trips to Sturgis, he’d leave a note on the fridge that said: “You know what you can and can’t do. I trust you’ll make the right decision.”

I remember thinking, beginning at age 10, that I most certainly did not know what I could or could not do. But I figured it out. When I was 18, I told my dad (and grandma and grandpa and sister) that I was moving to Boston. When dad said, “No, you’re not.” I said, “Yeah, I am.” And I did. But only because I didn’t know I couldn’t. His note—you know what you can and can’t do. I trust you’ll make the right decision—forced me to learn to trust myself to make the right decisions even when what’s “right” is not so clear. That saying on the fridge may be one of his greatest gifts to me.

Though I’m guessing he did not think so, as I drove off for Boston just as those flying saucers were prepared to launch.

My dad could also be astonishingly kind, thoughtful, tender, and vulnerable (I also have firsthand experience with this). I remember the first time he responded to something I said with: “That’s deep.”

I was in 4th grade when I wrote a story about a little girl who traveled to distant lands to gather all the seeds of hatred in the world. She knew if she could collect every seed and bury them in a magical garden, they would grow into a beautiful field of flowers. But she had to face great winds and impossible challenges. In the end, she gathered every single seed and planted each one in the magical garden, but was astonished when they didn’t grow. This made her cry. When she opened her eyes, the water from her tears made every seed rise. In the end, it was a beautiful field of flowers.

I won the Ohio state award for that story.

“That’s deep,” he said from the driver’s seat of his baby blue van, likely with a cig in hand, when I read it to him. We were on our way to Columbus to the award ceremony at some fancy hotel, just my dad and me. I didn’t know what he meant by “that’s deep” (I was in 4th grade, my mom had recently left), but I could tell by the way he said it that he thought it was cool. We sat together in the hotel’s ballroom. When they called my name, I stood up on my little shaky knees to collect my blue ribbon and walked back to the table. He said, “I’m so proud of you.”

Not long after I moved to Boston in 1998, I drove back to visit him. When I left, he told me: “If you leave, you can never come back.” But no matter what, I always reached back for a way to connect with him, even when it was hard. He told me I could meet him at Put-in-Bay, so I did. He was camping there for the weekend. I parked in the lot and took the ferry over. He was waiting for me by the dock, waving as I coasted in. We stopped at the store and loaded up on snacks and beer. Back at his campsite, we made a fire and sat up late talking. He may have shared a couple of those beers with me. There was not really such a thing as a “drinking age” for us, no more than there was really such a thing as a “curfew” or a “driving age.” He taught me to drive when I was 11 or 12. It was easier for him to kick back and have a couple of cold ones on our way home from the farm.

But back to our campsite in Put-in-Bay: My dad didn’t understand why I moved to Boston. And there were lots of things I did not understand about him. But we sat across the fire until late in the night, talking “deep,” connecting more like old friends than like father and daughter. When I snuggled into the homemade bed in the back of his van, I slid that very tiny window open and called out to him in his tent: I love you, dad.

The next day, he dropped me off at the ferry. He cried when he hugged me goodbye, and some weeks later, he showed up in Boston in his van loaded with all my stuff. If he was Captain Hook in a maggot-infested hat, he was simultaneously Peter Pan.

My dad and I both married into large families, but our family of origin is very small. When my sister and I were little, we’d go to the farm every weekend and for most of the summer. My grandma would always have a big pot of something on the stove, potatoes were usually involved, and whether we sat down to breakfast, supper, or dinner (because lunch wasn’t a thing), our plates were always overfull. We’d look around, and my grandpa or dad would say: “It’s a full family reunion!” Both my grandparents were only children. My dad was an only child. And back then, it was just me and my big sister. That was all of us.

With a family that small, my dad held center stage in the sky of our lives; a unique star in the constellation from which I come and to which I, too, will return. I know he’ll leave the lights on, the music blasting, and a fridge full of beer—as he once did actually do for Dan and me when we came in for Christmas one year and stayed at my Grandparents’ house. When Dan turned into the bottom of the crunchy gravel driveway, we could already hear the Christmas carols blasting from the road. We walked into a line-up of his latest homemade brews waiting for us, a giant bouquet, and yes, a fridge full of beers. My dad loves Dan.

Over the years, he visited me in almost all the cities I lived in: Boston, New York, he never made it out to see me in Venice Beach, but he loved Colorado and visited many times. In 2011, he came out by himself to attend one of the weekend spiritual retreats hosted by my community. I owned and operated a yoga studio back then, and we held meditation retreats. Some of the deepest conversations we ever had happened over that weekend. More recently, when dad and Jayne visited us in New Jersey, we had a blast in Cape May, slurping oysters, and yes, of course, having cold ones. I met him one morning for coffee on the patio overlooking the ocean. We had a special connection. For the past 8 years, I have never missed a Sunday call or a chance to go deep with him. We never made it back to Put-in-Bay together, but we never stopped trying to reach toward each other despite our differences, which are many.

My dad had an outsized impact on my life, like dads often do. He shaped me so totally by the things he did and didn’t do. I’ve always been sensitive, and was probably simultaneously loved and wounded by him more than most, though no one more deeply than my sister. And maybe that’s what deep love does: breaks us into a million pieces so we can reshape ourselves into the people we hope to become. My dad’s death hit me hard this week. This Emley bloodline ends with us. My Dad was the last of this “Emley” line, along with my sister and me.

I want to ask him again the questions he never answered, which are many. I want to pin him down over a campfire and talk to him about that saying: “You know what you can and can’t do. I trust you’ll make the right decision.” What? Did he intend for that to be the Zen koan that follows me through life? What’s “the right decision” when what’s right is not always so clear? But my dad was not a “pinned down” kind of guy. He was the guy leathered up on his Harley, packed for a couple of weeks with “his boys” in Sturgis, roaring down the road, heart wide open. Which is a little like what his death feels like to me right now.

About two weeks ago, I was accepted into a PhD program. I didn’t know I couldn’t get a PhD, so I applied, got the funding through a fellowship in Philadelphia, and it looks like I can and will get a chance to write that book I’ve always wanted to. I shared my dissertation, which is the book proposal, with my dad. It’s deep. He got it right away. He was so excited. The day before he fell, he left me a voice message: “I can’t wait to read your book. I’m so proud of you,” he said. And he gifted me with one last nickname on that voice message, in his slow, lowered tone sort of way, when he said, “Congratulations DOC.”

While my sister and I are like two of his many sides, I couldn’t be happier knowing that while she was always his closest jeepin’ buddy and very best nurse, now I get to become his DOC.

I love you dad.